The Hill

This is the hill that the kids came to in their cars all those years ago, after football games, after Friday night dances, and I can almost hear the giggling and the urgent exhortations. Boys and girls parking beneath the oil derricks on this desolate piece of land, a giant hump right in the middle of the city, lit by no light but the moon, disturbed by no sound but the grind and screech of the big oil pumps, sucking life from the hill like huge iron mosquitoes. The oil had mostly dried up ten years earlier, but a few pumps remained to make sure that every drop was sucked out. A lot of the derricks were still there, too, standing silent watch, ten-story weathered wooden lattices, relics of the drilling, no longer needed but not worth tearing down. The pumps huddled indifferently under their bases, pumping always.

Once you got to the top and parked the car, the view was breathtaking. This was before the streetlights were orange, and in the night the city stretched like a glittering sequined sheet all the way to the harbor, and the black ocean beyond could have been the very edge of the universe. You felt like you were flying, just standing there next to the car. I did, anyway. I might have been the only kid who actually saw the view, because even though I had a car, I never took a girl up there, to watch the submarine races, as we used to call it. I cruised it enough times, though, to know what it looked like, and I felt good up there alone, above it all, needing no one.

It's the steepest hill in the region, and back then the pavement ended halfway up. Above that were just the twisting oil company access roads, dirt and gravel. No one lived up here, the derricks your only witness, except for the occasional squad car. Tonight as I walk, high-priced apartments line the freshly blacktopped roads, cheaply built boxes put here to cash in on that view, contoured into fancy-looking architectural shapes through the magic of styrofoam. The hill has been remade, too, primped up with landscaping and terraced lots for the houses, cut sharply into the earth. The derricks are all gone now, and the few stubborn oil pumps are hidden artfully behind stands of palms and local shrubs.

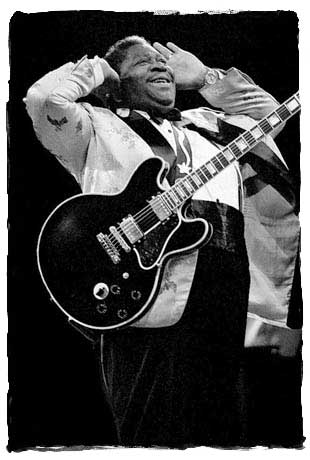

Once there was a nightclub at the very top of this hill. You'd drive along the deserted road in total darkness for a quarter-mile, you'd be aware of music playing somewhere, then abruptly you'd come upon a dirt parking lot lit by a few bare floodlights on makeshift poles. At the far end of the lot was the nightclub, looking like an island of corruption. An impossibly garish neon sign blinked

It was a low-slung cinderblock building with a boardwalk across the front of it, and a western style rustic wooden rail, like a hitching post. The bar served beer and shots, the bands played R&B and there were pool tables in the dark nether reaches. It might have been called The Hilltop Club, or The Rendezvous, or The Ron-Day View. There's no trace of it now, and I can't find anyone who remembers.

The hill had its own police department, company security left over from the oil boom, and maybe that's why the ID check at the door was not as rigorous as in the city below. For whatever reason, my friends drank there. Come on, Jones, the Lost Boys would say. They don't care how old you are, as long as you're spendin' money. I didn't see the fascination, and my fear of being thrown out was greater than my curiosity. I regret not going now, like so many things I didn't do.

In the end, I played in the band there, so I saw the place anyway, from the inside. I was too afraid to go in there just to see if I could fool them, but it was OK to do it if they paid me. I was not old enough to be working there, but no one ever asked about that. On stage I was a screaming showoff, shouting the blues like I meant it, but during the breaks I disappeared into the shadows, the better not to get found out and ejected. The irony of this behavior eluded me at the time. Strangely, none of my smartass friends ever saw me perform there, and eventually I came to wonder if they really ever went there.

Now I live in the shadow of the hill, and tonight I cruised it, like I used to. I don't know what happened to the old roads. They're not merely gone - their spirit is erased. There are guardrails and asphalt where once there were abandoned jalopies and loose gravel. Somehow, intersections and street signs have been contrived. The seedy nightclub has been razed and at the top, there's a little park, a lookout point with a stone wall around the perimeter, concrete benches and a statue. Even the park is two-thirds paved.

I leave the car a few blocks down and walk up toward the park. I wonder if any of the boys and girls who used to make out here in cars are living in these town homes, and if so, are they living with the ones they made out with? When I reach the top there are teenagers there, some couples, some groups. I'm pretty sure I know what has drawn them here, but they are safely contained in the bright enclosure, so their natural urges are stymied.

I stand at the stone wall, and the view is still breathtaking. The streetlights below are mostly orange now - is that what makes it less magical? Or is it that we know each other better now, the city and me? I own a piece of it, and it owns a piece of me. I think about flying over the city, like I did when I was a kid, but instead I just feel like I'm falling, and in fact I stagger back from the stone wall, catching myself before I actually take off. After that I leave the teenagers behind, as I always have, and go back to my car.

When I get there, I stand by the side of the road and take in the unauthorized view for a moment. The city has grown. It is so big and bright now that it eclipses the stars and dims the moon. It is full of living, dying, trying, crying. And out past the harbor, the very edge of the universe seems closer than ever.